Easter 2C: Doubting Thomas…Or Not!

By: The Rev. Marshall A. Jolly

Doubting Thomas: a tale of skepticism, suspicion, and contempt—or at least that’s what we’re supposed to believe. In reality, we’ve gotten far more mileage out of the label “doubting Thomas” than we have from the meaning of the story itself. And yet, every year on the Second Sunday of Easter, we hear this story. In fact, this is one of the few passages in the three-year cycle of the Revised Common Lectionary that never changes. Every year, we journey through Lent and Holy Week, arriving at Easter Sunday with an interchangeable combination of Matthew, Mark, and Luke as our guides with John occasionally appearing along the way. But on this and every Second Sunday of Easter, we always hear from the twentieth chapter of John’s Gospel.

There is much fertile ground for preaching and teaching this text by following the trope of doubt—both in the text and in our lives. On closer reading, it becomes clear that Thomas’s doubt is not the exception, but the rule. Much the same is true in our own lives of faith. We all have moments—some longer than others—of doubt. It is important to note that Jesus never condemns or rebukes Thomas for his doubt and indeed, lovingly reminds both Thomas and us, “Do not doubt, but believe (John 20:27).” Preachers and teachers who follow this exegetical path will also find several good commentaries and other resources, such as the Feasting on the Word commentary series, or through several of the helpful resources provided weekly by TextWeek.com (oh, and an unsolicited plug: if you don’t know about the wonderful weekly preaching and teaching resources provided by The Text This Week, do yourself a favor and check them out!)

For my part, however, I find flowing from this passage a different but no less pervasive aspect of human identity being brought to bear: blame.

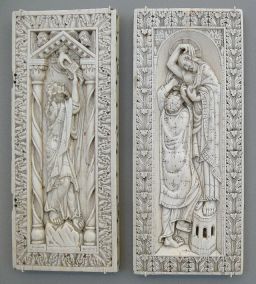

Although there are no overt mentions of the disciples blaming Thomas for failing to believe, this passage has been preached and taught as an exercise in blaming the “other” in innumerable ways. As early as the late 4th and early 5th centuries CE, St. John Chrysostom wrote that Thomas “is held to blame” for his unbelief at the Apostles’ assertion that they had seen the Risen Lord.[1] Artwork dating to the early 6th century also portrays Thomas as an obstinate, incorrigible doubter. The famous “Incredulity of Saint Thomas” is a fixture among the mosaics at the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, Italy.

The Patristic authors and classical artists aren’t alone in their contempt for Thomas. History is teeming with scores of (often bloody) examples of Christians rushing to position ourselves for Jesus and against anyone or anything we decide is against Jesus. And in Thomas’s case, doubting Jesus is just close enough to being against Jesus to wind up with a less-than-glamorous remembrance.

We know this “us versus them” dynamic all too well. If we can assign blame to the “other” political party or the “other” religious sect or the “other” ideology, then we can create for ourselves a cozy (albeit false) blanket of security, thinking ourselves immune from whatever interpersonal or religious or societal ills we’ve hocked at our enemies.

The Buddhist mystic and author Pema Chödrön writes eloquently and provocatively about our need to blame others in her book, When Things Fall Apart:

We habitually erect a barrier called blame that keeps us from communicating genuinely with others, and we fortify it with our concepts of who’s right and who’s wrong. We do that with the people who are closest to us and we do it with political systems, with all kinds of things that we don’t like about our associates or our society. It is a very common, ancient, well-perfected device for trying to feel better. Blame others… Blaming is a way to protect your heart, trying to protect what is soft and open and tender in yourself. Rather than own that pain, we scramble to find some comfortable ground.[2]

Was Thomas the only person to doubt Jesus’ resurrection? Of course not. In fact, everyone doubted it! Was Thomas lacking in moral fortitude? Hardly. After all, Thomas’s affirmation of the Resurrected Christ as “My Lord and my God” is perhaps the most powerful statement of faith among any of the disciples. No, Thomas is our scapegoat; he’s our “fall guy.” And like it or not, we’ve all met him, and some of us know him well.

Thomas is the embodiment of the “other” that we blame for the problems facing our religions and our societies. Thomas is the one we saddle with blame so we can protect our hearts from vulnerability, from pain, and perhaps even from the parts of ourselves we’ve spent our lives trying to ignore and outrun.

The 19th century Danish philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard said that our fears, our anxieties, and our insecurities lay the groundwork for sin because it is from these things that we are led to absolutize our values, identifying ourselves as “right” and everyone and everything else as “wrong,” in an attempt to satiate those very same fears, anxieties, and insecurities.[3]

Perhaps, then, it is fitting after all that we hear this very same tale of Thomas every year on the Second Sunday of Easter—fitting because maybe we need Thomas to convict us of more than our doubts. Perhaps we also need Thomas to bear witness to all that is “other” in our world, blamed for an ever-expanding litany of sins, but in the end summoning the faith and the courage to proclaim, “My Lord and my God!”

[1] John Chrysostom, “Homily 87 on the Gospel of John.”

[2] Pema Chödrön, When Things Fall Apart (Boulder: Shambhala Publications, 2000), 100.

[3] Søren Kierkegaard, The Concept of Anxiety: A Simple Psychologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic Issue of Hereditary Sin, 1844. Trans. Walter Lowrie, 1944.

The Rev. Marshall A. Jolly (@MarshallJolly) is the rector of Grace Episcopal Church in Morganton, North Carolina. He earned a BA in American studies from Transylvania University and a Master of Divinity and Certificate in Anglican Studies from Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. His published work includes essays on Christian social engagement, theology in the public square, and preaching, appearing most recently in the Journal of Appalachian Studies and the Anglican Theological Review. He is a frequent contributor to The Episcopal Church’s “Sermons that Work” series, and is the editor of “Modern Metanoia.” He enjoys hiking and otherwise exploring the nearby Appalachian foothills with his wife Elizabeth.